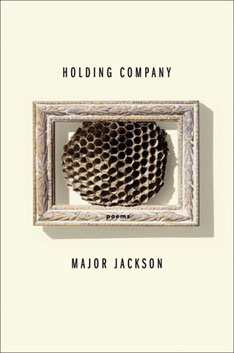

In Holding Company, Major Jackson explores art, literature, and music as a kingdom, or an empire, a dark, seductive force in our lives. In an effort to understand desire, beauty, and love as transient anodynes to metaphysical loneliness, he invokes Constantine Cavafy, Pablo Neruda, Anna Akhmatova, and Dante Rossetti.

In Holding Company, Major Jackson explores art, literature, and music as a kingdom, or an empire, a dark, seductive force in our lives. In an effort to understand desire, beauty, and love as transient anodynes to metaphysical loneliness, he invokes Constantine Cavafy, Pablo Neruda, Anna Akhmatova, and Dante Rossetti.

Reviews

The Hudson Review

Winter 2011, Vol. 63 Issue 4

The Elements of Style (excerpt) by Mark Jarman

In his first two collections of poetry, Leaving Saturn and Hoops, Major Jackson showed himself to be in thrall to a dense, allusive rhetoric, constantly seeking to follow a narrative thread. The result was always a rich mix of contemporary and classical reference, as you find in the poetry of Melvin Tolson, and sharp appraisal of urban life, with an eye like Gwendolyn Brooks’s. And though I never thought I would say such a thing, the attachment to narrative, to telling a clear story, kept his language in check. It helped the poet toward a clarity that he would just manage to attain, but the poems were hobbled. They wanted to take flight into a more inventive realm. With his third book, Holding Company, Major Jackson has slipped the surly bonds of narrative and given freedom to his lyric voice. At the same time, he has achieved a compression otherwise missing from his earlier work. He has done this in a series of ten-line poems, which resemble nothing so much as curtal sonnets. The book’s epigraph from Robert Lowell’s sonnet about T. S. Eliot, first published in Notebook, then revised ultimately for History, is not the only acknowledgement of Lowell’s influence. Lowell, too, found in his unrhymed, quasi-blank verse sonnets a release into lyricism and pursuit of the memorable and penetrating line, while risking obscurity. The other epigraph is from Pier Paolo Pasolini’s long poem “Plan of Future Works,” in which the Italian poet and filmmaker seemed to embrace the ambiguity of his own life as represented in his poetry: “neither the sign nor the existing thing matters.” That looks like permission simply to let the language have its way, to let ’er rip, clarity be damned.

I gave the bathtub purity and honor, and the sky

noctilucent clouds, and the kingfisher his implacable

devotees. I gave salt & pepper the table, and the fist

its wish for bloom, and the net, knotholes of emptiness.

I gave the loaf its slope of integrity, the countertop

belief in the horizon, and mud its defeated boots.

I gave morning triumphant songs which consume my pen,

and death its grief which is like a midsummer thunderclap.

But I did not give her my tomblike woe though it trembled

from my white bones and shook the walls of our home.

The title of this, the second poem in the volume, is “Creationism.” I can’t tell you why, but I can guess that it has to do with the poet’s acknowledgement of his own powers as a maker, a creator. The name “Creationism,” for the pseudo-science which is meant to counter evolution, has been appropriated. It keeps its connotation—it can’t lose it—but the poem gives it a new denotation. In this way, the word is yanked from its narrative, and the poet gives us something close to pure lyric expression, the kind which Hart Crane, one of Robert Lowell’s own models, sought and achieved. Hart Crane’s voice, which at times in his poetry seemed almost to transcend clarity, is echoed in many of the poems in Holding Company. In fact, considering the literal meaning of the title, it is invested in the style Major Jackson has created for himself. And Crane is surely part of the company these poems are keeping. I hear the echo in the second half of “Narcissus”: How many hours have I spent crushing mangrove leaves, turning my face to the unbearable grandeur of this heat-soaked sky? When I spun around, I felt filled with birds. Still, I returned, wallowing in the brothels of myself. I thought of my life, caressing more ruins. There is no doubt in my mind or ear that the poetry Major Jackson offers us in Holding Company—unashamedly lyrical, in flight from narrative, layered with allusion and homage—sounds different from any other being written today. MORE